An article published in Nature on 20th January highlights the good news regarding chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). These are Ozone-depleting substances and are also known to warm the atmosphere thousands of times more efficiently than carbon dioxide. You are perhaps aware of the Ozone hole over the Arctic. The finger was pointed towards CFCs, hence there was a huge effort to eliminate them by replacing them with HFCs.

CFCs also greatly increased the Arctic Warming

There is a new revelation regarding CFCs. As explained by the article in Nature …

most of the research on these chemicals has focused on their effects on the planet’s protective ozone layer — especially over the Southern Hemisphere, where they are responsible for the formation of the Antarctic ozone hole, says Mark England, a climate scientist at Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. He co-authored the study, published on 20 January in Nature Climate Change1, which he says is “really reframing a lot of the discussion on a more global basis”.

England and his colleagues compared climate simulations both with and without the mass emission of CFCs that began in the 1950s. Without CFCs, the simulations showed an average Arctic warming of 0.82 °C. When the presence of ozone-depleting compounds was factored in, that number jumped to 1.59 °C. The researchers saw similarly dramatic changes in sea-ice coverage between the two sets of model simulations. By running the models with fixed CFC concentrations while varying the thickness of the ozone layer, the team was able to attribute the warming directly to the chemicals

The good news is that the Ozone hole observation motivated us to get rid of CFCs.

Side Note: The paper’s conclusion is still a debatable connection. Susan Strahan, an atmospheric scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, says that the work is “interesting and provocative”, but she is not yet convinced of its conclusions. A stronger argument could be made, she continues, if the team had been able to provide a clear physical explanation for the modelled amplification.

This is all background for what comes next.

Chlorofluorocarbon and Hydrofluorocarbon

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) are fully or partly halogenated paraffin hydrocarbons that contain only carbon (C), hydrogen (H), chlorine (Cl), and fluorine (F). Since they greatly impacted Ozone and caused the Ozone hole, we needed a replacement. So Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) were developed as a replacement. They do not harm the ozone layer.

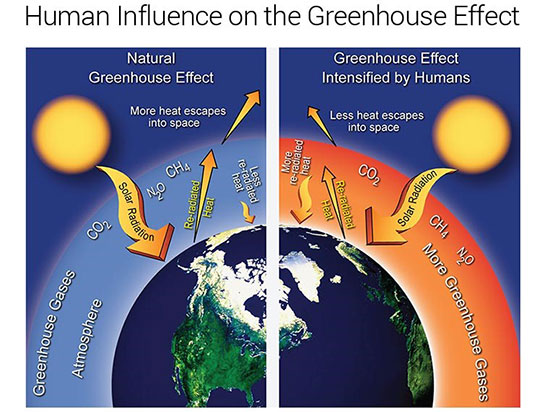

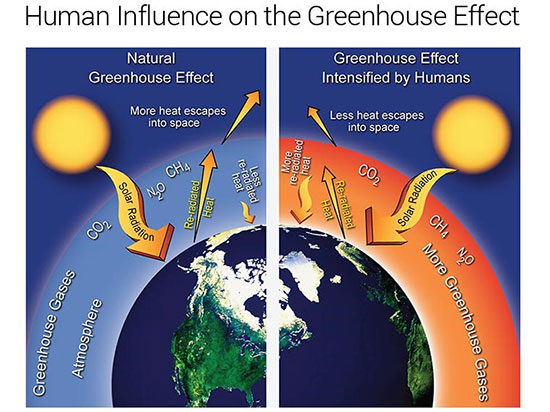

Unfortunately, both CFCs and also HFCs are greenhouse gases that contribute to global warming. The fact that we replaced CFCs with HFCs is good news for Ozone. It is not such great news for global warming.

Once the climate impact was fully appreciated, a legally-binding accord was created in 2016 to phase out hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs).

How is the HFC phase-out going?

On the 21st January, the day after the above Nature article, the following study was published in Nature Communications.

Increase in global emissions of HFC-23 despite near-total expected reductions

Yes, this is the “Oh F**k” moment.

Starting in 2015, China and India, who dominate global HCFC-22 production (75% in 2017), set out ambitious programs to reduce HFC-23 emissions. These measures should have seen global emissions drop by 87% between 2014 and 2017. Instead, this latest paper reports that atmospheric observations show that emissions have increased. In 2018 were higher than at any point in history.

What happened?

Given the magnitude of the discrepancy between expected and observation-inferred emissions, it is likely that the reported reductions have not fully materialized. There may be substantial unreported production of HCFC-22, resulting in unaccounted-for HFC-23 by-product emissions.

HFC-23 Impact

HFC-23 is a very potent greenhouse gas. One tonne of its emissions is equivalent to the release of more than 12,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Had these HFC-23 emissions reductions been as large as reported, the researchers estimate that the equivalent of a whole year of Spain’s CO2 emissions could have been avoided between 2015 and 2017.

Study Author comments

Dr Matt Rigby, who co-authored the study, is a Reader in Atmospheric Chemistry at the University of Bristol and a member of the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment(AGAGE), which measures the concentration of greenhouse gases around the world, said:

“When we saw the reports of enormous emissions reductions from India and China, we were excited to take a close look at the atmospheric data.

“This potent greenhouse gas has been growing rapidly in the atmosphere for decades now, and these reports suggested that the rise should have almost completely stopped in the space of two or three years. This would have been a big win for climate.”

Dr Kieran Stanley, the lead author of the study, visiting research fellow in the University of Bristol’s School of Chemistry and a post-doctoral researcher at the Goethe University Frankfurt, added:

“To be compliant with the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol, countries who have ratified the agreement are required to destroy HFC-23 as far as possible.

“Although China and India are not yet bound by the Amendment, their reported abatement would have put them on course to be consistent with Kigali. However, it looks like there is still work to do.

“Our study finds that it is very likely that China has not been as successful in reducing HFC-23 emissions as reported. However, without additional measurements, we can’t be sure whether India has been able to implement its abatement programme.”

Dr Rigby added:

“The magnitude of the CO2-equivalent emissions shows just how potent this greenhouse gas is.

“We now hope to work with other international groups to better quantify India and China’s individual emissions using regional, rather than global, data and models.”

Dr Stanley added:

“This is not the first time that HFC-23 reduction measures attracted controversy.

“Previous studies found that HFC-23 emissions declined between 2005 and 2010, as developed countries funded abatement in developing countries through the purchase of credits under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Clean Development Mechanism.

“However, whilst in that case, the atmospheric data showed that emissions reductions matched the reports very well, the scheme was thought to create a perverse incentive for manufacturers to increase the amount of waste gas they generated, in order to sell more credits”.

Further Reading

- Nature (20th January 2020) – Ozone-depleting gases might have driven extreme Arctic warming

- Nature Communications (21st January 2020) – Increase in global emissions of HFC-23 despite near-total expected reductions

- Bristol University Press Release related to HFC emissions report – Emissions of potent greenhouse gas have grown, contradicting reports of huge reductions