A new study has been published that looks into how climate change is stratifying our oceans. Titled “Increasing ocean stratification over the past half-century” and published within Nature Climate Science on Sept 28, 2020 some of the co-authors are well-known names such as Michael E Mann of Penn State and John Abraham of the University of St Thomas in Minnesota.

John has written a clear concise description of it all. It is of course tempting to add my own spin, but this is the co-author, so I will defer to him to explain it.

JOHN ABRAHAM – HOW CHANGING OCEANS IMPACT US

My international research team and I just published a major scientific study in the journal Nature Climate Change that deals with how water moves throughout the oceans and how changes to the climate are affecting these water flows.

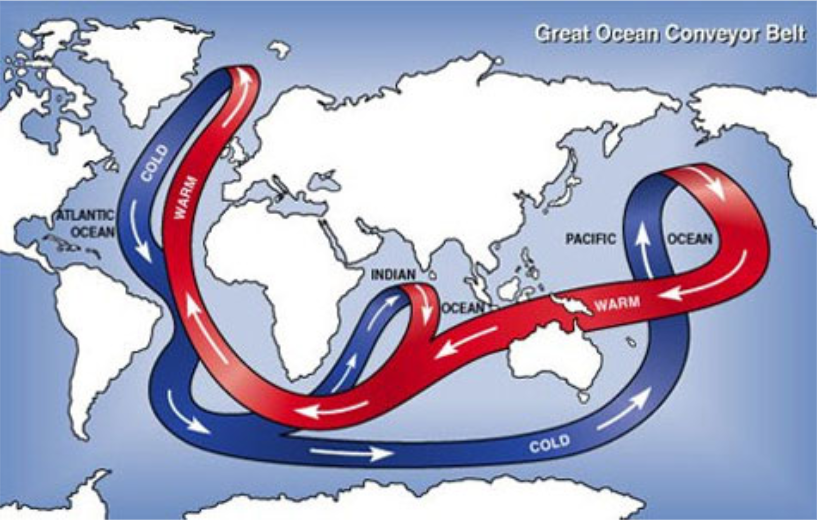

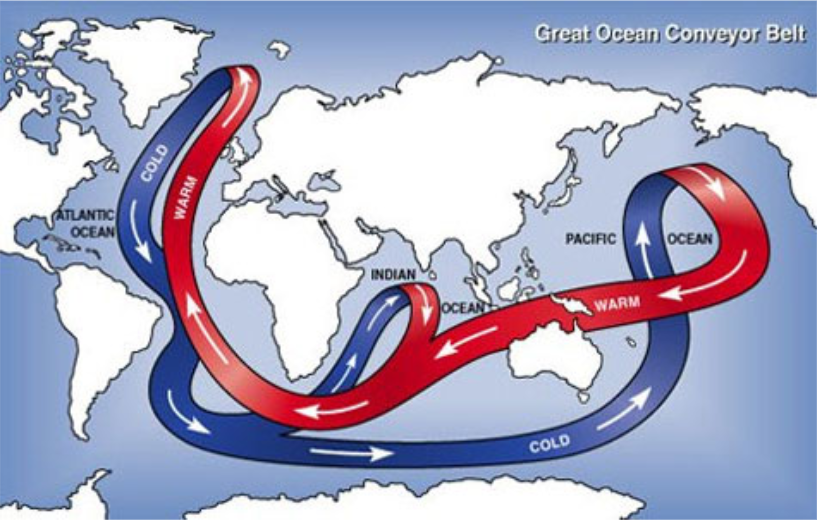

Oceans cover 70% of our planet. They are vast and affect the weather we experience, even in Minnesota. Ocean waters are not stationary – they flow across the globe and they even rise and fall (from the ocean surface to the ocean floor). Surface waters that fall downward to the ocean floor are called “down-welling” flows, whereas “upwelling” flow refers to water deep in the ocean that rises toward the surface.

Ocean waters become stratified. This means lighter, less dense water sits near the surface while more dense waters lie near the ocean bottom. What causes water to be more or less dense? Two things: temperature and saltiness.

We have all heard the phrase “heat rises.” And this is really true. If you heat a fluid (like water), it becomes less dense, and wants to rise. Conversely, when water cools, it becomes more dense and tends to fall. Because of this, we typically find the warmest waters near the ocean surface and the coldest waters down below.

Saltiness also matters. The saltier water is, the heavier it is. Consequently, oceans tend to have salty water near the bottom and fresher, less salty waters at the surface.

The combined effects of temperature and saltiness causes ocean stratification.

As the planet warms because of human emission of heat-trapping gases, we expect there may be changes to the stratification. For example, as the ocean temperatures increase, it is the waters near the surface that heat fastest. This makes the ocean surface less dense and less likely to fall downward.

When water does fall through the ocean (flows from the surface downward), it brings with it heat. Conversely, when waters rise in the oceans, they carry with them cold temperatures and lots of nutrients. In fact, some of the world’s best fishing areas are regions with upwelling waters – sea life thrive in these areas.

What scientists want to know is whether the ocean stratification is increasing or decreasing. That is, are upwelling and down-welling increasing or decreasing? This is the central question of the research that was just published. We found that stratification is increasing … This means it is becoming harder for surface waters to down-well (and also harder for deep waters to rise to the ocean surface). We discovered that the upward and downward water flows have decreased by more than 5% over the past few decades. The reason for the decrease is global warming – the extra heat from global warming is heating up the top layers of the oceans and making them less dense.

Why do we care? Because the oceans affect our weather. With ocean waters more stable, it means surface water will remain at the ocean surface for longer periods of time, heat up more, and this makes storms more severe. Think of the impact this will have on hurricanes, for instance. Hurricanes gain their strength from the ocean temperatures. A more stable ocean, with a surface layer that is warmer, will cause storms to be stronger. The effects on weather will become larger as global warming proceeds.

There is good news, however. We humans can reverse this trend. We can make decisions to use energy more wisely and to use more clean/renewable energy. The hardest part is getting started. But once we decide to take actions on climate change, things will begin to get better.