I mentioned it yesterday when writing about the WMO Bulletin. The 2019 Emissions gap report is now published and it is not good news. It is of course related to the production gap report that I was writing about last week.

There was once a time when we could seriously address the issue in a gradual manner. That time has now gone. Decades of denial mean that we now face a crises that only drastic action can address.

9 Key Points

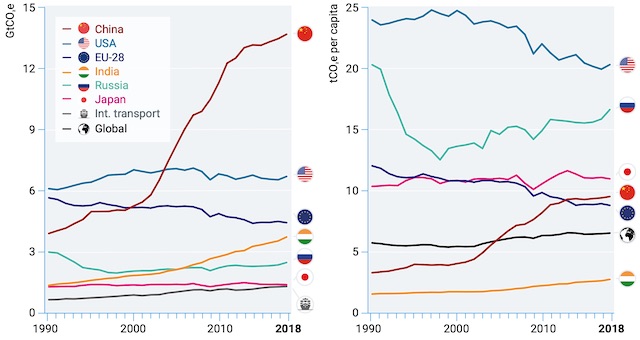

1. Greenhouse Gas emissions continue to rise, despite scientific warnings and political commitments.

- Emissions have risen at a rate of 1.5 per cent per year in the last decade

- Total GHG emissions, including from land-use change, reached a record high of 55.3 GtCO2e in 2018

- Fossil CO2 emissions from energy use and industry, which dominate total GHG emissions, grew 2.0 per cent in 2018, reaching a record 37.5 GtCO2 per year.

- There is no sign of GHG emissions peaking in the next few years; every year of postponed peaking means that deeper and faster cuts will be required.

- By 2030, emissions would need to be 25 per cent and 55 per cent lower than in 2018 to put the world on the least-cost pathway to limiting global warming to below 2 ̊C and 1.5°C respectively

2. G20 members account for 78 per cent of global GHG emissions.

Collectively, they are on track to meet their limited 2020 Cancun Pledges, but seven countries are currently not on track to meet 2030 NDC commitments, and for a further three, it is not possible to say.

- As G20 members account for around 78 per cent of global GHG emissions (including land use), they largely determine global emission trends and the extent to which the 2030 emissions gap will be closed. This report therefore pays close attention toG20 members.

3. Although the number of countries announcing net zero GHG emission targets for 2050 is increasing, only a few countries have so far formally submitted long-term strategies to the UNFCCC.

- Five G20 members (the EU and four individual members) have committed to long-term zero emission targets, of which three are currently in the process of passing legislation and two have recently passed legislation. The remaining 15 G20 members have not yet committed to zero emission targets.

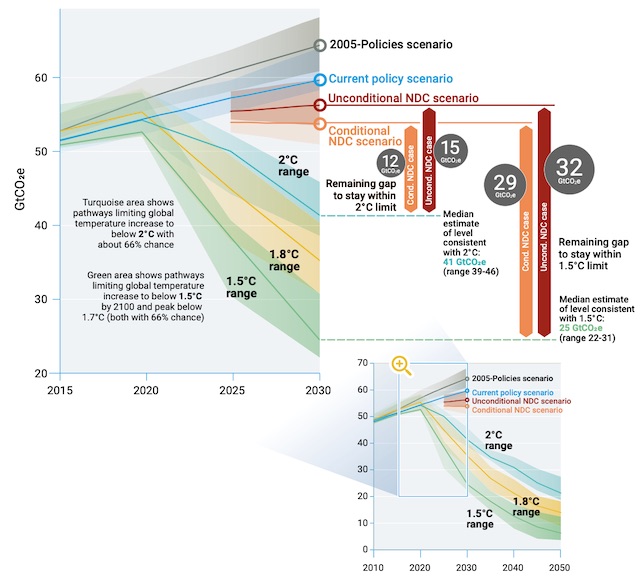

4. The emissions gap is large.

In 2030, annual emissions need to be 15 GtCO2e lower than current unconditional NDCs imply for the 2°C goal, and 32 GtCO2e lower for the 1.5°C goal.

- The emissions gap between estimated total global emissions by 2030 under the NDC scenarios and under pathways limiting warming to below 2°C and 1.5°C is large (see Figure ES.4). Full implementation of the unconditional NDCs is estimated to result in a gap of 15 GtCO2e (range: 12–18 GtCO2e) by 2030, compared with the 2°C scenario. The emissions gap between implementing the unconditional NDCs and the 1.5°Cpathway is about 32 GtCO2e (range: 29–35 GtCO2e).

- If current unconditional NDCs are fully implemented, there is a 66 per cent chance that warming will be limited to 3.2°C by the end of the century. If conditional NDCs are also effectively implemented, warming will likely reduce by about 0.2°C.

5. Dramatic strengthening of the NDCs is needed in 2020.

Countries must increase their NDC ambitions threefold to achieve the well below 2°C goal and more than fivefold to achieve the 1.5°C goal.

- The ratchet mechanism of the Paris Agreement foresees strengthening of NDCs every five years. Parties to the Paris Agreement identified 2020 as a critical next step in this process, inviting countries to communicate or update their NDCs by this time.

- Given the time lag between policy decisions and associated emission reductions, waiting until 2025 to strengthen NDCs will be too late to close the large 2030 emissions gap

- Had serious climate action begun in 2010, the cuts required per year to meet the projected emissions levels for 2°C and 1.5°C would only have been 0.7 per cent and 3.3 per cent per year on average. However, since this did not happen, the required cuts in emissions are now 2.7 per cent per year from 2020 for the 2°C goal and 7.6 per cent per year on average for the 1.5°C goal. Evidently, greater cuts will be required the longer that action is delayed.

6. Enhanced action by G20 members will be Necessary

Although many countries, including most G20 members, have committed to net zero deforestation targets in the last few decades, these commitments are often not supported by action on the ground.

7. Decarbonizing the global economy will require fundamental structural changes.

Such changes should be designed to bring multiple co-benefits for humanity and planetary support systems.

- By necessity, this will see profound change in how energy, food and other material-intensive services are demanded and provided by governments, businesses and markets.

- This year’s report explores six entry points for progressing towards closing the emissions gap through transformational change in the following areas: (a) air pollution, air quality, health; (b) urbanization; (c) governance, education, employment; (d) digitalization; (e) energy- and material-efficient services for raising living standards; and (f) land use, food security, bioenergy.

8. Renewables and energy efficiency, in combination with electrification of end uses, are key to a successful energy transition and to driving down energy-related CO2 emissions.

- Expanding Renewable Energy for electrification.

- Phasing out coal for rapid decarbonization of the energy system

- Decarbonizing transport with a focus on electric mobility

- Decarbonizing energy-intensive industry

- Any transition at this scale is likely to be extremely challenging and will meet a number of economic, political and technical barriers and challenges. However, many drivers of climate action have changed in the last years, with several options for ambitious climate action becoming less costly, more numerous and better understood.

- A key example of technological and economic trends is the cost of renewable energy, which is declining more rapidly than was predicted just a few years ago

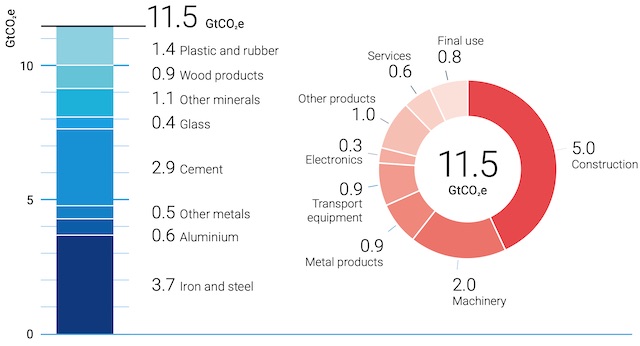

9. Demand-side material efficiency offers substantial GHG mitigation opportunities that are complementary to those obtained through an energy system transformation.

- In 2015, the production of materials caused GHG emissions of approximately 11.5 GtCO2e, up from

5 GtCO2e in 1995. The largest contribution stems from bulk materials production, such as iron and steel, cement, lime and plaster, other minerals mostly used as construction products, as well as plastics and rubber. - mitigation potential …

- Product lightweighting and substitution of high- carbon materials with low-carbon materials to reduce material-related GHG emissions associated with product production, as well as operational energy consumption of vehicles.

- Improvements in the yield of material production and product manufacture.

- More intensive use, longer life, component reuse, remanufacturing and repair as strategies to obtain more service from material-based products.

- Enhanced recycling so that secondary materials reduce the need to produce more emission-intensive primary materials.

Why This report now?

The UN Climate Change Conference COP 25 (2 – 13 December 2019) will take place in Madrid next week. It will be run under the Presidency of the Government of Chile and will be held with logistical support from the Government of Spain.

The conference is designed to take the next crucial steps in the UN climate change process. This report is designed to focus minds at the conference.

Crucial climate action work must be taken forward in areas including finance, the transparency of climate action, forests and agriculture, technology, capacity building, loss and damage, indigenous peoples, cities, oceans and gender.

Emissions Gap Report – How Much Time is Left?

Further Reading

From this portal you can jump into easily accessible data and insights.

- The primary page for the UN Emissions Gap Report

- The report itself. Download …

- The full report (it is not a small document)

- The Exec Summary