The Paris Agreement last May has been hailed a success, and in many respects it was indeed exactly that because it resulted in a completely unprecedented agreement between most of the nations on the planet to take decisive steps to combat climate change.

The aim was to hold climate change below 2 degrees Celsius and to “pursue efforts” to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. However, the one big flaw here is that what was agreed is not enough to accomplish those goals. Now please don’t misunderstand that, what has been agreed is of vital importance and needs to still be done. The issue is that if such a goal were to be achieved then rather a lot more would be needed.

This has been highlighted within a recent paper in Nature where the authors explain …

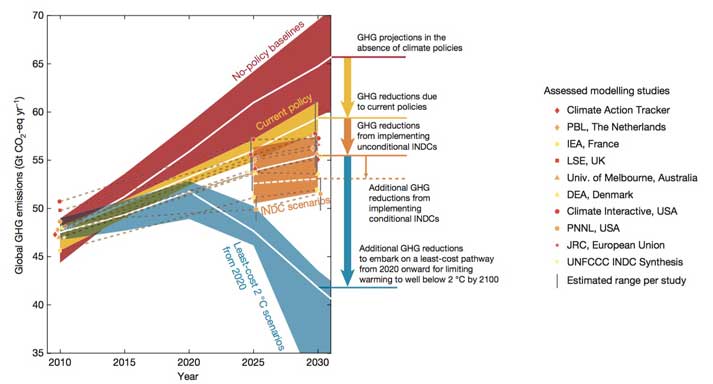

The Paris climate agreement aims at holding global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius and to “pursue efforts” to limit it to 1.5 degrees Celsius. To accomplish this, countries have submitted Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) outlining their post-2020 climate action. Here we assess the effect of current INDCs on reducing aggregate greenhouse gas emissions, its implications for achieving the temperature objective of the Paris climate agreement, and potential options for overachievement. The INDCs collectively lower greenhouse gas emissions compared to where current policies stand, but still imply a median warming of 2.6–3.1 degrees Celsius by 2100. More can be achieved, because the agreement stipulates that targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are strengthened over time, both in ambition and scope. Substantial enhancement or over-delivery on current INDCs by additional national, sub-national and non-state actions is required to maintain a reasonable chance of meeting the target of keeping warming well below 2 degrees Celsius.

It basically all pans out like this …

Now let’s explain the above scenarios.

The Scenarios illustrated above represent alternative images of the future, or “[stories] about what may happen in the future”. They are not predictions nor are they forecasts, but instead are tools to understand how the future might unfold under a consistent set of assumptions. Within their paper they use the following four

No-policy baseline scenarios. This is the do nothing scenario. These are emissions projections that assume that no new climate policies have been put into place from 2005 onwards.

Current-policy scenarios. This is where we are without the Paris agreement being implemented. These consider the most recent estimates of global emissions and take into account implemented national policies.

INDC scenarios. Basically this is what happens if everything agreed in Paris is actually implemented. These project how global GHG emissions evolve under a successful implementation of the INDCs. (Side note: INDCs = Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, basically the amount the various nations pledged to reduce CO2 by)

2 °C scenarios. This is the ideal and is what happens if we keep warming to well below 2 °C, keeping open the option of strengthening the global temperature target to 1.5 °C.

All scenarios are expressed in terms of billions of tonnes of global annual CO2-equivalent emissions (Gt CO2-eq yr−1). CO2 equivalence of GHGs has been calculated by means of 100-year global warming potentials.

In summary …

- Paris does greatly help and is a truly historic achievement , but it really is not going to be enough.

- Adhering to the INDCs after 2030 will be very very challenging to achieve.

- The polite term they use is “societal challenge” and that is perhaps an appropriate way to encapsulate our unwillingness as a species to take decisive meaningful action while we still can

Will we rise to the challenge?

We have of course started to do so, but I suspect it may prove not to be enough, and we will need to take even more drastic action. A general realisation that this is the case might not dawn until it is too late.