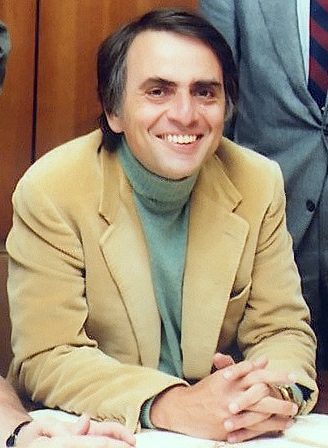

If, and I confess it is possible, you are wondering … “Who?”, well OK here is a quick biographical summary (that I just shamelessly nicked from his Wikipedia page) …

Carl Edward Sagan (/ˈseɪɡən/; November 9, 1934 – December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, astrophysicist, cosmologist, author, science popularizer and science communicator in astronomy and natural sciences. He spent most of his career as a professor of astronomy at Cornell University where he directed the Laboratory for Planetary Studies. He published more than 600 scientific papers[2] and articles and was author, co-author or editor of more than 20 books. He advocated scientific skeptical inquiry and the scientific method, pioneered exobiology and promoted the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI).

Sagan is known for his popular science books and for the award-winning 1980 television series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, which he narrated and co-wrote.[3]The book Cosmos was published to accompany the series. Sagan wrote the novel Contact, the basis for a 1997 film of the same name.

So anyway, I’m drifting a tad off topic, time to focus.

If you wish to have a few quick easy rules for detecting bullshit, then you should consider embracing Carl Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit, because it is a fabulous bit of clear distinct guidance … (Oh and yes, he was polite, so he used the word “baloney” instead of “bullshit”).

Within his rather famous book, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark (link to public library) there is a chapter entitled “The Fine Art of Baloney Detection,” where he describes how easily we can all be fooled, and then goes on to explain that scientists have been trained to cope with this reality. They have been equipped with what he terms a “baloney detection kit” – in other words, here is some very practical guidance on how to work out what is and is not bullshit.

Key Point: He argues that this is not simply for scientists, but is for all of us to use whenever faced with ideas or claims. … I agree.

So when faced with any ideas or wild claims, then here is his well-proven cognitive toolkit that you can deploy

- Wherever possible there must be independent confirmation of the “facts.”

- Encourage substantive debate on the evidence by knowledgeable proponents of all points of view.

- Arguments from authority carry little weight — “authorities” have made mistakes in the past. They will do so again in the future. Perhaps a better way to say it is that in science there are no authorities; at most, there are experts.

- Spin more than one hypothesis. If there’s something to be explained, think of all the different ways in which it could be explained. Then think of tests by which you might systematically disprove each of the alternatives. What survives, the hypothesis that resists disproof in this Darwinian selection among “multiple working hypotheses,” has a much better chance of being the right answer than if you had simply run with the first idea that caught your fancy.

- Try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours. It’s only a way station in the pursuit of knowledge. Ask yourself why you like the idea. Compare it fairly with the alternatives. See if you can find reasons for rejecting it. If you don’t, others will.

- Quantify. If whatever it is you’re explaining has some measure, some numerical quantity attached to it, you’ll be much better able to discriminate among competing hypotheses. What is vague and qualitative is open to many explanations. Of course there are truths to be sought in the many qualitative issues we are obliged to confront, but finding them is more challenging.

- If there’s a chain of argument, every link in the chain must work (including the premise) — not just most of them.

- Occam’s Razor. This convenient rule-of-thumb urges us when faced with two hypotheses that explain the data equally well to choose the simpler.

- Always ask whether the hypothesis can be, at least in principle, falsified. Propositions that are untestable, unfalsifiable are not worth much. Consider the grand idea that our Universe and everything in it is just an elementary particle — an electron, say — in a much bigger Cosmos. But if we can never acquire information from outside our Universe, is not the idea incapable of disproof? You must be able to check assertions out. Inveterate skeptics must be given the chance to follow your reasoning, to duplicate your experiments and see if they get the same result.

Links

- The Carl Sagan Portal

- I would recommend you read his book … The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark

- Amazon US here

- Amazon UK here

- (And no, I’m not earning $$ from those links, I just want to encourage you to read the book)

Sagan was known for slinging a lot bullshit himself. Here’s two of his most famous pieces of bull … his predictions about the Kuwaiti oil field fires and his depiction of the fate of the Library of Alexandria in Cosmos. I heard him comment once that we should be wary of celebrity scientists. He wasn’t bullshitting then.

You are a shit vomitter!

You are clearly having a bad day.

Total BS. What BS. You know nothin, Carl Sagan.

I’m sure he knew how to spell ‘nothing’, which obviously is at least one thing more than you know, you ignorant prick.