What Exactly Does this new study do?

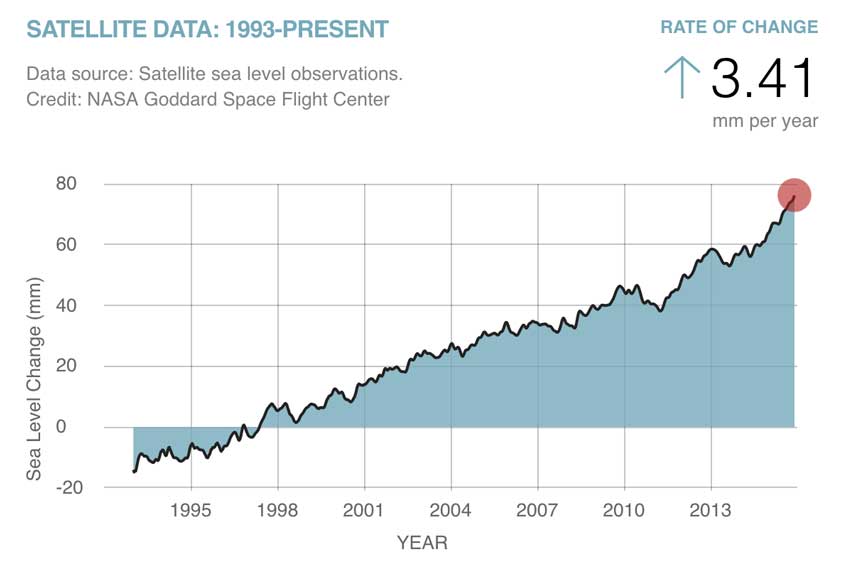

We have precise measurements via satellite, so we do know exactly where sea level is now and hence how fast it is rising globally. The problem has been that the records in the pre-satellite era have been a bit limited in several ways …

- It was not continuous in time – people simply recorded what a tidal gauge reported at a specific moment in time

- It was very localised, hence there was an uneven coverage

To deal with these shortcomings the study authors took the previous data and applied recent advances in solid Earth and geoid corrections for individual tide gauges, and also took into consideration our better understanding of the geographical representation of ocean internal variability.

What they have found from this reassessment is that the trends reported for the pre-satellite era are actually smaller than previously reported. This means that when you combine that with the very precise satellite measurements, then we clearly have a distinct acceleration in the rate of sea level rise that is about three times faster that the 20th century rate.

Numbers

The specifics are as follows …

Our reconstructed GMSL [Global Mean Sea Level] trend of 1.1 ± 0.3 mm⋅y−1 (1σ) before 1990 falls below previous estimates, whereas our estimate of 3.1 ± 1.4 mm⋅y−1 from 1993 to 2012 is consistent with independent estimates from satellite altimetry, leading to overall acceleration larger than previously suggested.

Why was it previously wrong?

There are specific problems with taking readings from tide gauges at face value, and unless you consider these, then the readings you get do not tell you the complete story.

Tide gauges are grounded on land. This means that they affected by the vertical motion of the Earth’s crust, caused both by natural processes and human activities. Natural processes to consider would be a glacier melting and thus causing the land to rise, and also of course earthquakes. Human activities that have an impact include things such as groundwater depletion and dam building.

Rather obviously tide gages are also local and not global.

This new study is not the first to attempt to correct such known challenges with tide gauges, so we do need to ask ourselves what went wrong with the previous attempts at doing this.

The most cited studies from the last decade combined static spatial patterns constrained from satellite altimetry observations with temporal information from tide gauges into a global curve. That yielded a 20th century GMSL [Global Mean Sea Level] rise of 1.7 ± 0.3 mm·y−1.

Another approach averaged regional sea level curves obtained from stacking rates of individual station data into a global reconstruction, leading to an increase of 1.9 ± 0.3 mm·y−1 since 1900.

The results were problematic and clearly too linear and larger than estimates of the sum of individual contributions, so something was clearly not quite right. Using the latest and best available information to correct tide gauge data they utilised a area-weighting average technique to arrive at this new estimate.

How do we know that this new study is better?

How confidence are they that they have got it right? If previous attempts are wrong, then what confidence can we have in this latest study?

This is the secret sauce here. We have accurate satellite measurements from 1993 onwards, so what happens if they utilise this latest approach with the tidal gauge data for that same period, and then compare that to what the satellite readings tell us?

This is what happens …

During the period 1993–2012, our reconstruction yields a trend of 3.1 ± 1.4 mm·y−1 (P ≥ 0.97), similar to the values obtained from independent satellite altimetry measurements

Bottom Line here: Sea level is rising, and the reassessment of the pre-1993 tidal gauge data reveals that the rate at which it is rising has greatly accelerated since the 1990s.

I believe that the best term that perhaps sums that up is something akin to “yikes!”.