A new study published within science advances throws a spotlight upon how sea-level rise can impact human society. They do this by throwing a spotlight upon an actual example.

The Isles of Scilly are an archipelago 25 miles (40 kilometres) off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. It was once, in the not too distant past a far larger island, but because of rising sea-level, it has been fragmented. As recently as 400–500 AD rising sea levels flooded the central plain.

A few fascinating observations …

- At certain low tides the sea becomes shallow enough for people to walk between some of the islands

- Ancient field walls are visible below the high tide line off some of the islands

If sea-level has globally been static in that period, then why has this happened?

It is because the whole of southern England has been steadily sinking in opposition to post-glacial rebound in Scotland; this has not only drowned the Isles of Scilly, but has caused the rias (drowned river valleys) on the southern Cornish coast, e.g. River Fal and the Tamar Estuary.

The new study looks back on this example of a rising sea-level devastating human society and reveals what happens. It points towards how the rising sea-level due to climate change will impact human society on a global scale

Nonlinear landscape and cultural response to sea-level rise

Published within Science Advances on Nov 4, 2020, the stud was conducted by researchers at the University of Exeter in the UK.

Details

(The following details have been provided by the University of Exeter)

Rising sea levels will affect coasts and human societies in complex and unpredictable ways, according to a new study that examined 12,000 years in which a large island became a cluster of smaller ones.

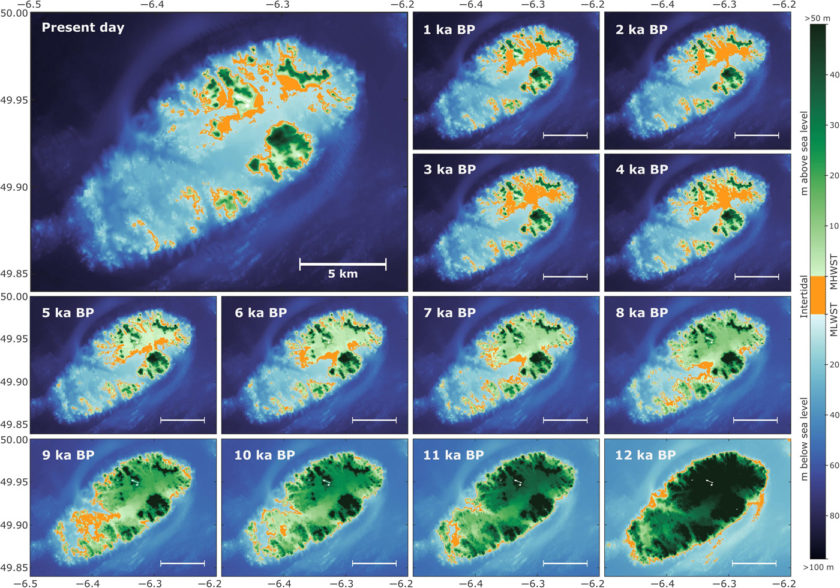

Researchers reconstructed sea-level rise to produce maps of coastal changes at thousand-year intervals and found that today’s Isles of Scilly, off the UK’s south-west coast, emerged from a single island that only became the current configuration of more than 140 islands less than 1,000 years ago.

The study, led by the University of Exeter in partnership with Cornwall Archaeological Unit, Cardiff University and 14 other institutes, found that changes in both land area and human cultures happened at variable rates, and often out of step with the prevailing rate of sea-level rise.

With climate change now driving rapid sea-level rise, the team says the effects will not always be as simple as a forced human retreat from coasts.

“When we’re thinking about future sea-level rise, we need to consider the complexity of the systems involved, in terms of both the physical geography and the human response”

“The speed at which land disappears is not only a function of sea-level rise, it depends on specific local geography, landforms and geology.”

“Human responses are likely to be equally localised. For example, communities may have powerful reasons for refusing to abandon a particular place.”

lead author Dr Robert Barnett, of the University of Exeter.

The researchers developed a new 12,000-year sea-level curve for the Isles of Scilly, and looked at this alongside new landscape, vegetation and human population reconstructions created from pollen and charcoal data and archaeological evidence gathered. The new research extends and enhances data collected by the Lyonesse Project (2009 to 2013), a study of the historic coastal and marine environment of the Isles of Scilly.

These findings suggest that during a period between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago land was rapidly becoming submerged. In response to this period of coastline reorganisation, people appeared to adapt to, rather than abandon, the new landscape.

By the Bronze Age (after 4400 years ago), the archaeological record suggests the area had a permanent population – and instead of leaving the islands, it appears that there may have been a “significant acceleration of activity”.

The reasons for this are unclear, but one possibility is that new shallow seas and tidal zones provided opportunities for fishing, shellfish collection and hunting wildfowl.

This period of rapid land loss happened at a time of relatively slow sea-level rise – because lots of Scilly’s land at that point was relatively flat and close to sea level.

The study found that between 5000 and 4,000 years ago, land was being lost at a rate of 10,000 m2 per year, which is equivalent to a large international rugby stadium. However, about half of this land was turning into intertidal habitats, which may have been able to support the coastal communities.

“This new research confirms that the period immediately before 4,000 years ago saw some of the most significant loss of land at any time in the history of Scilly — equivalent to losing two-thirds of the entire modern area of the islands”.

Charlie Johns (Cornwall Archaeological Unit) co-director of the Lyonesse Project

After 4,000 years ago, the island group continued to be submerged by rising sea levels, even during modest (e.g., 1 mm per year) rates of sea-level rise.

“It is clear that rapid coastal change can happen even during relatively small and gradual sea-level rise,”

“The current rate of mean global sea-level rise (around 3.6 mm per year) is already far greater than the local rate at the Isles of Scilly (1 to 2 mm per year) that caused widespread coastal reorganisation between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago.

“It is even more important to consider the human responses to these physical changes, which may be unpredictable.

“As can be seen today across island nations, cultural practices define the response of coastal communities, which can result in polarised agenda, such as the planned relocation programmes in Fiji versus the climate-migration resistance seen in Tuvalu.

“In the past, we saw that coastal reorganisation at the Isles of Scilly led to new resource availability for coastal communities.

“It is perhaps unlikely that future coastal reorganisation will lead to new resource availability on scales capable of supporting entire communities.

“More certain though, is that societal and cultural perspectives from coastal populations will be critical for responding successfully to future climate change.”

lead author Dr Robert Barnett, of the University of Exeter.

The research was funded by a grant from English Heritage (now Historic England) to the Cornwall Council Historic Environment Service (now Cornwall Archaeological Unit). Outputs from the original project (The Lyonesse project: A study of the historic coastal and marine environment of the Isles of Scilly (2016)) are also available from the Cornwall Archaeological Unit.

Direct Quotes from the paper itself

…While a contemporary logical response to reduction in land area and resource availability might be to retreat and seek a new place to live, on Scilly the drive to adapt was greater and the response may have been cultural rather than physical. Responses to external change are embedded within social groups, and adaptive responses are mutable and subjective. A sense of ownership and belonging is powerful, especially where change is experienced throughout multiple lifetimes and is, therefore, accepted as an inevitable part of the environment…

…As can be seen today across island nations, cultural practices define the adaptive response of coastal communities, which can result in polarized agendas, such as the planned relocation programs in Fiji versus the climate-migration resistance seen in Tuvalu. It is perhaps unlikely that coastal reorganization in coming centuries will lead to new resource availability on scales capable of supporting entire communities, as found on Scilly for past millennia. More certain though is that societal and cultural perspectives from coastal populations will be critical for developing holistic and successful adaptive responses to future climate change.