(The content of this posting has been derived from “The Conspiracy Theory Handbook”. Full credit belongs to Stephan Lewandowsky, and John Cook)

Real conspiracies do exist. Well-known examples includes …

- Volkswagen conspired to cheat emissions tests for their diesel engines.

- The U.S. National Security Agency secretly spied on civilian internet users.

- The tobacco industry deceived the public about the harmful health effects of smoking

How do we all know that these are real?

Internal industry documents, government investigations, or whistleblowers.

The dubious theories are the ones that are popular, persistent, and unsupported by evidence. Examples include JFK or the claim that 9/11 was an inside job. If your goal is to believe as many true things as possible, then how can you protect yourself in a world where wild unsubstantiated theories are popular?

How you think matters

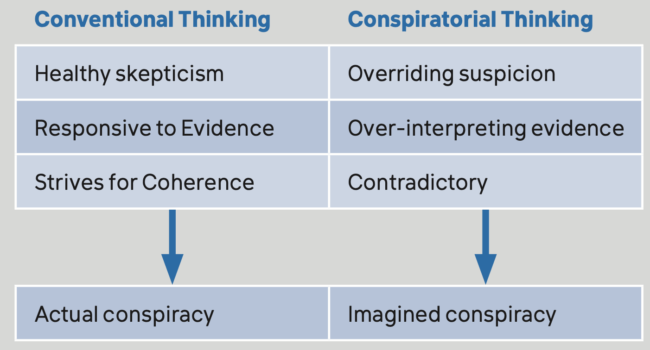

Real conspiracies get discovered through conventional thinking. In a contrast to that conspiratorial thinking is characterized by being hyperskeptical of all information that does not fit the theory, over-interpreting evidence that supports a preferred theory, and inconsistency.

Why are Conspiracy Theories popular?

Feeling of powerlessness

People who feel powerless or vulnerable are more likely to endorse and spread them.

Coping with threats

These ideas allow people to cope with threatening events by focusing blame on a set of conspirators.

Explaining unlikely events

For the same reason, people tend to propose conspiratorial explanations for events that are highly unlikely. Conspiracy theories act as a coping mechanism to help people handle uncertainty.

Disputing mainstream politics

Conspiracy theories are used to dispute mainstream political interpretations. Conspiratorial groups often use such narratives to claim minority status.

Social media amplifies conspiracy theorizing

Social media has created a world in which any individual can potentially reach as many people as mainstream media. The lack of traditional gate-keepers is one reason why misinformation spreads farther and faster online than true information, often propelled by fake accounts or “bots”. Likewise, consumers of conspiracy theories have been found to be more prone to “like” and share conspiracist posts on Facebook.

How can you spot a Conspiracy Theory that is most probably not true?

There are seven traits of conspiratorial thinking that should all be red flags for you to watch out for.

1. Contradictory

Conspiracy theorists can simultaneously believe in ideas that are mutually contradictory. For example, believing the theory that Princess Diana was murdered but also believing that she faked her own death. This is because the theorists’ commitment to disbelieving the “official“ account is so absolute, it doesn’t matter if their belief system is incoherent.

2. Overriding suspicion

Conspiratorial thinking involves a nihilistic degree of skepticism towards the official account. This extreme degree of suspicion prevents belief in anything that doesn’t fit into the conspiracy theory.

3. Nefarious intent

The motivations behind any presumed conspiracy are invariably assumed to be nefarious. Conspiracy theories never propose that the presumed conspirators have benign motivations.

4. Something must be wrong

Although conspiracy theorists may occasionally abandon specific ideas when they become untenable, those revisions don’t change their overall conclusion that “something must be wrong” and the official account is based on deception

5. Persecuted victim

Conspiracy theorists perceive and present themselves as the victim of organized persecution. At the same time, they see themselves as brave antagonists taking on the villainous conspirators. Conspiratorial thinking involves a self-perception of simultaneously being a victim and a hero.

6. Immune to evidence

Conspiracy theories are inherently self-sealing—evidence that counters a theory is re-interpreted as originating from the conspiracy. This reflects the belief that the stronger the evidence against a conspiracy (e.g., the FBI exonerating a politician from allegations of misusing a personal email server), the more the conspirators must want people to believe their version of events (e.g., the FBI was part of the conspiracy to protect that politician).

7. Re-interpreting randomness

The overriding suspicion found in conspiratorial thinking frequently results in the belief that nothing occurs by accident. Small random events, such as intact windows in the Pentagon after the 9/11 attacks, are re-interpreted as being caused by the conspiracy (because if an airliner had hit the Pentagon, then all windows would have shattered) and are woven into a broader, interconnected pattern.

Things to look out for when faced with a claim

Ask yourself questions like these …

- Do I recognize the news organization that posted the story?

- Does the information in the post seem believable?

- Is the post written in a style that I expect from a professional news organization?

- Is the post politically motivated?

A Vaccine for Misinformation

If you become aware that you can be misled then you can develop a resilience to conspiratorial messages. Being made aware of the flawed reasoning found in conspiracy theories, means that you may become less vulnerable to such theories.

Debunking

Fact-based debunkings

Fact-based debunkings show that the conspiracy theory is false by communicating accurate information. This approach has been shown to be effective in debunking the “birther” conspiracy which holds that President Obama was born outside the U.S. as well as conspiracy theories relating to the Palestinian exodus when Israel was established.

Source-based and empathy-based debunking

Source-based debunking attempts to reduce the credibility of conspiracy theorists whereas empathy- based debunkings compassionately call attention to the targets of conspiracy theories. A source-based debunking that ridiculed believers of lizard men was found to be as effective as a fact-based debunking. In contrast, an empathy-based debunking of anti- Semitic conspiracy theories that argued that Jews today face similar persecution as early Christians was unsuccessful.

Logic-based debunking

Logic-based debunkings explain the misleading techniques or flawed reasoning employed in conspiracy theories. Explaining the logical fallacies in anti-vaccination conspiracies has been found to be just as effective as a fact-based debunking: For example, pointing out that much vaccination research has been conducted by independent, publically-funded scientists can defang conspiracy theories about the pharmaceutical industry.

Links to fact checkers

Links to a fact-checker website from a simulated Facebook feed, whether via an automatic algorithmic presentation or user- generated corrections, effectively rebutted a conspiracy that the Zika virus was spread by genetically-modified mosquitoes.

How to talk to a conspiracy Theorist

Research into deradicalization provides useful insights into how to potentially reach conspiracy theorists.

Trusted messengers

Counter-messages created by former members of an extremist community (“exiters”) are evaluated more positively and remembered longer than messages from other sources.

Affirm critical thinking

Conspiracy theorists perceive themselves as critical thinkers who are not fooled by an official account. This perception can be capitalized on by affirming the value of critical thinking but then redirect this approach towards a more critical analysis of the conspiracy theory.

Show empathy

Approaches should be empathic and seek to build understanding with the other party. Because the goal is to develop the conspiracy theorist’s open-mindedness, communicators must lead by example.

Avoid ridicule

Aggressively deconstructing or ridiculing a conspiracy theory, or focusing on “winning” an argument, runs the risk of being automatically rejected. Note, however, that ridicule has been shown to work with general audiences.

One Last Word

Real conspiracies do exist. But the traits of conspiratorial thinking are not a productive way to uncover actual conspiracies. Rather, conventional thinking that values healthy skepticism, evidence, and consistency are necessary ingredients to uncovering real attempts to deceive the public.

Further Reading – The Conspiracy Theory Handbook

The contents of this posting have been distilled from The Conspiracy Theory Handbook.

That was written by Psychologist Stephan Lewandowsky, and John Cook from George Mason University. The original text is well-referenced and leans upon the best available peer-reviewed research.

I highly recommend reading the original. From there you can drill down into the actual research that underpins it all.